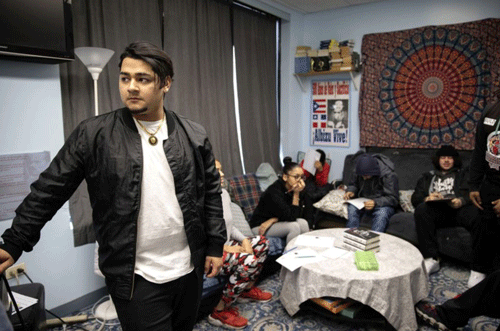

Every one of the 150 or so students at Dr. Pedro Albizu Campos High School had been labeled a failure. Yet here, in this unique charter school tucked behind and above a storefront steps away from Humboldt Park, they thrive.

The students, most between 18 and 21 years old, hustle in and out of tiny classrooms furnished not with orderly rows of desks and chairs but with overstuffed sofas and colorful tapestries, group work tables and soft lighting. “Healing spaces,” in the school’s parlance. They laugh with their teachers, they kid one another, some are hunkered down over laptops, deep into their classwork. Hugs, hand slaps, fist bumps. Teenagers.

The exuberance belies the struggles that brought most of them to this school, one of 19 campuses across Chicago that make up the Youth Connection Charter School. It’s a nonprofit consortium of small community schools founded in 1997 and dedicated to educating students who have dropped out, or are about to drop out, of traditional high schools.

“Without this place, I’d probably just be working minimum wage somewhere,” said Wilfredo Claudio, 21, who struggled to keep going to classes at the nearby public high school, Roberto Clemente Community Academy. A counselor suggested he transfer to Campos, where he’s now on track to get his diploma. Without the switch: “Man, I probably would’ve made some really bad decisions.”

The role for Tribune readers

The Tribune Editorial Board’s “Chicago Forward: Young lives in the balance” initiative is putting a spotlight on the challenges of reaching Chicagoland’s disconnected youth — the 16- to 24-year-olds at risk of being out of school, out of work and far from the path toward a productive and healthy life. We are calling on you, our readers, to submit proposals for new ideas, partnerships and solutions to this problem, which ultimately costs Chicago up to $2 billion a year in lost earnings, lower economic growth, lower tax revenues and higher government spending.

Today, we consider the role of schools and education. Campos High School, founded in 1972 by Puerto Rican activists in the neighborhood and later brought under the umbrella of the Alternative Schools Network and YCCS, exemplifies the power of the school environment in connecting young people with services and opportunities lacking in other areas of their lives. Over and over, educators and researchers have emphasized to us the importance of “wraparound services” — counse– lors, mentors, on-site child care, programs to address trauma and depression, meals. Those services support students emotionally and physically so they can stay on track academically, graduate and live productive lives. Essentially, it’s using the in-school setting to help kids deal with out-of-school issues, such as poverty, family turmoil and gun violence.

“There’s a bunch of stuff going on outside of school,” Campos student Jessica Vazquez, 17, told us during a visit to the school in January, “but then you come inside and it’s peaceful here. It’s like a whole big family.”

‘I lost my homie last year’

Last year, Gwain Brown, 16, who was a sophomore at Campos and a close friend of Vazquez’s, was shot to death while he and another male were standing outside a store on South Cicero Avenue. “I lost my homie last year,” she said, choking back tears as she described how the school paused its normal routines to mourn her friend’s death. “They support you emotionally.”

Beyond the normal struggles of being a teenager, beyond the added stress that poverty brings and beyond the double threat of gangs and drugs on the streets, each gunshot — no matter the target — causes a ripple effect of trauma in our neighborhoods. For too many young people, school is their only oasis.

Yet an environment as nurturing as the one we witnessed at Campos — with multiple counselors, small classes and the flexibility a charter school offers — isn’t possible in most public schools.

Why not? Money.

Don’t count on City Hall and Springfield

This is the point where we’d like to say that every school district should have endless funds to hire countless counselors and other trained professionals to nurture each child with unmet needs through to graduation. We support that dream. And we believe that wraparound services at more schools would make a profound difference for those youth most at jeopardy of slipping beyond our reach.

So we should look to City Hall for more millions? If only. The enormous and legally enforceable debts and unfunded pension obligations of CPS and City Hall are crushing other priorities.

Should we look instead to Springfield? Same story: State government is drowning in pension and other debts. Yes, lawmakers in 2017 passed a new statewide public school funding formula that directs more money to needier districts, including CPS. But it took decades of political wrangling to pull off. And the next recession, whenever it arrives, will threaten that new funding.

The fierce urgency of now

Our most vulnerable youth don’t have decades to wait for Springfield to debate incremental changes to public policy. They don’t have precious school time to give up while union leaders play to national cameras and taxpayers flee. They are in crisis now, making decisions each day about whether to go to class or skip again, to seek help or slip away.

That’s why charter schools such as Campos and other nonprofit organizations that depend on public and private grants, remain so essential. In Chicago, in Illinois, the public sector cannot do this alone. Only expanded involvement from the private sector, in tandem with government efforts, can make a difference for the most imperiled young people of this metropolis.

Consider the wide-reaching Communities in Schools, a national organization that in Chicago partners with 175 CPS schools. It provides a range of dropout prevention and student enrichment programs that have been proven to keep kids in school and, in some cases, boost math and reading skills.

Or initiatives such as WOW (for Working On Wo– manhood) counseling groups, managed by the Chicago organization Youth Guidance. WOW serves about 2,400 young women in seventh through 12th grades in 40 Chicago schools with significant risk factors for drop out or delinquency.

When we sat in recently with a WOW group of six juniors at Benito Juarez Community Academy, a CPS high school in Pilsen, the young women began with an accounting of the “thorns and roses” they’d experienced over the previous week — the good and bad that lifted them up or dragged them down.

The group applauded when Juanita announced her rose, her achievement of a 3.6 grade-point average, higher than she’d expected, and 100% attendance during the school year so far. After the group session, she told us that WOW had been instrumental in pu– lling it off.

“There used to be times when I felt like I’d never be able to make it this far in my junior year,” Juanita said. “If we didn’t have the WOW group here, I’d probably be lacking in my classes, doing some of the work but not all of it. Now I’m thinking about college.”

Editorials reflect the opinion of the Editorial Board, as determined by the members of the board, the editorial page editor and the publisher.

By Chicago Tribune Editorial Board